The Data Cycle: Teaching on the CBCS Syllabi during the Pandemic

Published: 04/05/2021 on Out of the Blox: Sanglap Journal

‘Why am I doing this? What am I changing? Am I doing any good at all?’ In my professional teaching career in Higher Education of over six years, I have often found myself confronted with these questions.

As I sit here almost regretting my hasty promise to Arunima to write this piece, I am drowning in a virtual whirlpool of overlapping exam schedules, batch-wise email addresses, and timings and uploading to portals, and the only thing that I can say with any certainty about my experience as a college teacher under WBES during the pandemic academic year is that we are woefully understaffed. Not simply for the online mode of examination, but also for the new (running on its third year now) CBCS system, with its ambitiously wide syllabus and its multiple-component examination scoring system. This becomes increasingly apparent as we advance further into the system, with higher semesters unfolding and new batches coming in, leading to multiple semesters running simultaneously which results in a constant rush to meet multiple deadlines.

In 6+ years of college teaching, as a teacher of English literature, I have drawn the following inferences:

- Students who have scored above ninety percent in English in their school-leaving examinations often struggle to construct simple sentences in English. While this is not true of all students, the number is still significant enough to raise questions on the state of English learning in school. So where does the rot lie? My money is on the increasingly general tendency to make education a scoring system rather than a system that focuses on what the pupils actually learn. A common rebuff I hear these days is that one needn’t learn the colonizer’s language to be deemed educated or respectable. True enough, but that doesn’t explain why a student aiming to take up English language and literature as a bachelor’s degree course is unsure about the basic grammar of the language. And if this is what happens in one subject, one can’t help but wonder about the gap between scoring and learning in other subjects as well.

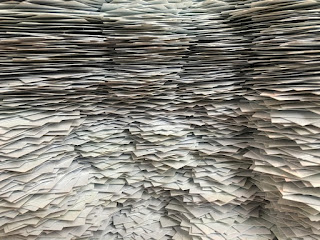

- Something of that mindset is carried over in the CBCS system where all the extra columns of data contribute to making scoring marks easier but without any scope of originality of thought and analysis. Don’t get me wrong. I am not against students scoring marks, seeing that I was one not so long ago, but I am exhausted by the endless cycle of reading made-to-order essays and compiling more and more data. Compile, upload, save, print, repeat. It’s an endless cycle.

- The CBCS system is, on paper, a more flexible system. But it does not take into consideration the disparity across India in student-teacher ratio and student demography, nor is the individual college teacher given any autonomy in designing their courses and assignments. During the early days of lockdown last year, before the official directives for online classes came in, I experimented with assigning out of syllabus short stories and poems to my tutorial group, asking them to write their responses. At least sixty percent made an attempt to come up with original responses, making grading a more joyous experience than it usually is. A system where departments/teachers are given more autonomy could actually encourage students to learn to express their own ideas rather than reproduce the learned by rote material of guidebooks. On the whole, I don’t think our education system is designed to make students think. As a result, we get the same rehashed material in the form of thousand-word essays submitted as projects. Producing a redundant cycle of grading and uploading of marks causing increasing disillusionment and constant exhaustion.

On a related note, I was privileged enough to not only have parents who enjoyed reading and inculcated that love in me, but also to go to schools that actively encouraged reading in the form of a weekly library class in the routine. When I was a school student, everybody read. Even friends who later on went on to study engineering and medicine. And they continue to read today. While in my classes I encounter an increasing number of literature students who don’t read. Neither in their mother tongues nor in the language they professedly ‘love’ enough to come and seek a Bachelor’s or Master’s degree in. As a student of literature myself, I have a naïve faith in the power of fiction to inculcate empathy, understanding, and imagination, the therapeutic ability to create one’s own inner world – qualities I believe are needed in today’s divided world. It’s unfortunate that this finds no place in anyone’s election manifesto, but we need more libraries. Instead, we get ballot-politics-driven cosmetic surgery of the education sector to garner quick brownie points– more colleges (without infrastructure), superficial syllabus changes, and the supposed choice-based credit system.

Under the CBCS system, all core and general papers have three components (four, when you count attendance but as a saving grace the University has been giving full attendance to everyone in lockdown) - internal assessment, tutorial, and theory. In the offline system, the teachers upload marks for attendance, internals, and tutorials. In the online mode, the attendance component has been replaced by theory/end semester exams which are now held online and arranged by the colleges/departments. The process for uploading these marks for all these different components is complicated. First, one must generate foil numbers for each of these components from the examination portal- generally one foil number per component per batch of students, but for bigger batches, there are often two or three or more foil numbers for every single component. Next, one must enter the subject and paper code for each component to make the marks entry. Then enter the details again to verify. And then enter the details for a third time to generate the statement of marks. This process is repeated for every single foil. Even without network crashes, which are frequent, uploading data for a single department might take two or three hours. The OTP for log-in is sent to a single phone registered to the institution, which means some 19 departments with one phone between them are trying to upload details of 50+ components (per department) in the limited period when the portal is open. At the end of the ordeal, one wonders why one studied literature (or anything) at all!

Ironically, in offline/non-quarantine mode, the supposedly digital CBCS system generates more paperwork than the previous system. While earlier an examiner filled up one big mark sheet per paper, also signed by the scrutineer, now there are the foil numbered sheets for each of the 2 or three components per paper, duly filled in and signed, and an equal number of portal generated statements for the examiner. And the scrutineer generates their own set. What with frequent server crashes, network glitches, and the disparity in teacher-student ratio, it seems to me that we have adopted a system we are not equipped for, demographically or technologically.

I did a quick math for our upcoming exams as I was writing this, and we have 37 components of marks to upload to the university portal at the end of March, and the number could go up to 58 if the university office splits up our two longer batches into separate foils. If this all sounds a bit technical for an article about teaching experience, it’s because the teaching part seems now to be subsumed by endless, redundant cycles of technicalities.

That last observation holds true in other areas of the job as well. For the last four years, my college has been preparing for National Assessment And Accreditation Council. Same data, different formats. Sent to X. Re-formatted and sent to Y. Edited and sent to Z. Sent to X again in a completely new format. And on and on the data cycle repeats. Because at the end of the day, what counts is not creativity, but data. One of my 2020 work-from-home highlights was converting above seventy documents from PDF to word files and then renaming them in the course of an evening. On the plus side though, I’ve learned all the MS Excel stuff that three years of actual clerical work for the Jadavpur University Department of English BA admissions didn’t teach me.

I was a bookish nerd as a student. I enjoyed going to college, sitting in the classes, watching my teachers open whole new worlds every day. I had assumed that the experience from the opposite side would also be as magical. But now, 6 years in, I find myself increasingly mired in a cycle of data and paperwork, and more paperwork. The CBCS system was supposed to make education more flexible. We have Honours papers broken into internal assessments and tutorials now, but all that they have come to mean is just more columns in the datasheet. Mechanically grading projects that are merely repetitions of the same old questions that have been asked. And a part of me can’t help but think- it would be fun to have a theatre workshop as a tutorial for the Shakespeare paper instead of writing the same rehashed thousand-word essay. But where is the time for that when we are speeding to meet university decreed deadlines? After all, what’s the material value of a theatre or a poetry workshop? Instead, the ‘project’ has become another exercise in the familiar book-learning dead-end. Perhaps one reason for this state of affairs is the imposing of the ‘science’ model on all disciplines, without taking into account the course objectives. The tutorial is after all the Arts stream’s substitute for the ‘Practical’ component in the science disciplines. This tendency spills over in other areas of academia as well. The requirements of promotion for college teachers involves, among other things, the stringent accounting for time spent inside classrooms, not heeding the time spent preparing for lessons or out-of-classroom interactions. The same tendency to quantify what are essentially qualitative concerns is seen in one of the criteria of NAAC, which tries to assess the mentor-mentee relationship and the quality of student counselling through MCQ surveys.

When the lockdown initially put a hold on regular schedules and examinations, I used the online medium to mix up things a little. Apart from the weekly assignments on out-of-syllabus fiction and poetry, I arranged a mini-seminar where the students read their own papers on film and television adaptations of Wuthering Heights and set ‘Google form’ quizzes to assess their understanding of in-syllabus texts in terms of current world events. After all, how could anybody teach Faulkner’s Dry September in 2020 without talking about George Floyd? When we did return to full-fledged regular classes and exams, albeit via Google Meet, I tried to use the tools of the digital mode to my (and I hoped, the students’) advantage. For my classes on Comedy as a genre, I edited clips out of Shakespeare productions and uploaded the video to my own channel. After a week, there were exactly five views. After the initial disappointment, I understood why. The system didn’t require my students to laugh at comedy or to appreciate comedy. It only required them to learn some words about comedy and reproduce them on paper.

And yet, I know that our students are capable of creativity if given the opportunity. One rewarding experience for me has been supervising the English drama/musical for the last three years. The calendar of the semester-divided year has now put this little breath of fresh air into question. Last year, we had to curtail one day of the programme to accommodate last-minute exam schedules that ran right up to Christmas. And yet, shouldn’t a true ‘choice’ based credit system include credit for innovative activities?

But whatever my impression of the system, I can’t deny that the journey has helped me in many ways to discover myself. Back in my own college days, I used to stare at my teachers with awe. I was sure I would never be able to talk by myself for a full forty-five minutes, and if I did, I thought I wouldn’t be assertive enough and for the first few months of my career, this second part was true enough. I remember being mistaken for a student by the library staff on my first day of work and being mistaken for a student by a candidate on my first invigilation, and I think it had more to do with how nervous I felt rather than how I looked. And then, to my surprise, I learned that I knew how to raise my voice. That I had things to say and I could talk for forty-five minutes and more, and people would listen. I’ve enjoyed hours inside classrooms that have gone a long way in compensating for all the tiresome, redundant, mechanical labour. I’ve discovered I’m not bad at my job. But the other lesson has been this, that sometimes, my abilities to connect and communicate depended on my students. This last lesson has been emphasized by the lockdown experience.

There’s a line in Andrew Marvell’s ‘The Garden’ where the poet declares that women’s beauty is nothing in comparison to the amorous greens of his precious garden. Apollo and Pan chased maidens, he says, but found in the end that the laurel tree and the reed were far more superior as sources of solace. This dismissive retelling of what are essentially stories of attempted rape always incites a sardonic comment from me when I am teaching the poem in class- nothing practiced but an automatic eye roll, a shared chuckle with the students. This semester however when I paused to declare how the speaker sounded like he was bitter about a bad rejection, I suddenly found myself unsure. I didn’t know these first semester girls, never interacted with them in a physical classroom, I couldn’t even see their faces (due to network issues, our students keep their cameras off and interact through the comment box or by unmuting themselves), and I wasn’t quite sure if I could be as informal through my laptop as I was when actually interacting with students in person. I had no way of knowing if they were laughing at my jokes. And sometimes, this feeling of uncertainty was true even in offline classrooms. Sometimes, the only questions I am asked at the end of a class are about potential examination questions or the selection of pages one should read for the exam. Sometimes, teaching is a two-way performance in which I am only as good as my audience. This is especially true for literature as we are dependent on teacher-student dialogues and interactions between students themselves. And I’m not sure that simply imposing the model of the physical classroom into an entirely different system can do justice to the discipline. Perhaps we need to devise a new set of tools for this ‘new normal’.

I’ve always wanted to share with my students the sense of wonder that I experienced (and still do) as a student of literature. Fresh off a grueling examination season that generated excel sheets quite proportional to the sense of futility it evoked, and facing another semester of speaking into the void of online classes, I only have one question. Does the data cycle have any space for wonder?

"Photo by Christa Dodoo on Unsplash"

All views expressed here belong to me and not to any institutions I am part of.

Comments

Post a Comment